- Home

- Robert Knuckle

The Flying Bandit Page 19

The Flying Bandit Read online

Page 19

When they got home in the middle of January Robert began again to dream about buying that bar in the Caribbean. He could move his family there and would never have to tell Janice the truth about his identity. And he’d never get discovered in those islands or be sent to jail.

By now he’d widened the scope of his dream. While he was in England, he’d talked to Mick Daglish about coming in as a partner with him. Mick had money and a true sense of adventure, and after Robert explained his proposition, he had responded very receptively. He told Robert to look into the idea and report back to him.

When Robert told Janice about Mick’s involvement in a possible partnership, she loved the idea. However, knowing Robert, she didn’t think it would ever actually happen.

After coming home from Europe, Robert was caught in the same old bind. He had great plans but he’d spent so wildly over there that, towards the end of January, he didn’t have much of his money left. It’s hard to conceive how so much money could disappear so quickly, but cocaine continued to be a major drain.

Needing cash, Robert began scouting around southern Ontario looking for some prospective targets in Mississauga, Barrie and Orillia, but nothing really appealed to him. It was hard to be satisfied with a run-of-the-mill bank job considering the success he’d enjoyed with the jewellery stores. What he really wanted was another million-dollar payday. That meant doing another Birks store.

Contrary to the prediction of the police, Robert didn’t consider doing Birks in Montreal. This time it would be the one in Ottawa in the Rideau Shopping Centre, right across the mall from Alyea’s Jewellers, the store that Robert had robbed on a dare the previous June. The holdup date was set for Friday, February 6.

The robbery was not a typically smooth Robert Whiteman performance. He and his accomplice (not Lee Baptiste) both behaved very badly. Robert jumped over the estate counter and demanded the key to the display case from sales clerk, Harman DeSouza. When DeSouza resisted, Whiteman grabbed him by the throat and threw him against the back wall. The sight of Robert manhandling DeSouza sent some of the customers in the store into a fit of panic. Attempting to keep them quiet, Robert’s partner pulled out his gun and began waving it around and yelling orders at them. An elderly woman standing near the partner didn’t take kindly to his shouting. She raised her cane as if to strike him, but reconsidered when he pointed his gun at her and waved her back.

Harman DeSouza’s lack of cooperation cost the bandits a lot of valuable time. When Robert finally did get the key to the showcase over thirty seconds had elapsed and he didn’t have time to steal as many trays as he had planned. With the clock ticking, Robert jumped back over the counter and fled out of the store with his assistant. While they were running down the service corridor a young man ran after them. The two thieves, hearing his footsteps, turned and trained their guns on him. The pursuer tried to come to a sudden halt, lost his balance, and fell. His girlfriend, watching from a distance, thought he had been shot and began to scream.

If that wasn’t enough confusion for one day, there was more waiting around the corner. As soon as they had discarded their disguises, Robert and his accomplice made their exit through the Rideau Centre near Eatons. On their way, they discovered the Ottawa Police were running a charity fund-raiser in the mall, called Jail and Bail. Local celebrities were put in a mock jail cell until they raised enough bail from their friends to be released. The concourse around the jail cell was crawling with police who were helping out with the fund-raiser. Robert and his pal had to walk right through them with their briefcase full of diamond rings.

From there they went to the Delta Hotel and met with their fence to celebrate. Before totalling the price tags on the jewellery Robert decided to keep a couple of pieces for himself, for what he termed a rainy day. When they added up the value of all the rest of the goods, Robert was disappointed that it only came to $160,000. After he paid his partner, there was barely $20,000 in it for himself.

After that painful setback, things got dramatically worse when he left the Delta Hotel and started driving home towards Pembroke. Distracted by his paltry end of the take, Robert was cruising along the Queensway talking to himself, when, around Kanata, he realized that his briefcase wasn’t in its usual place in the front seat beside him. Seeing it wasn’t anywhere in the car, he became very agitated. The guns, the wigs, the moustaches, the jewellery and the money were all in it. He pulled over and checked the car from stem to stern. Painfully it dawned on him that he had left it in the hotel room.

In a panic Robert raced back to the Delta only to find that the chambermaid had already cleaned the room. Frantically he went on a twenty-minute search from floor to floor looking for her. When he found her she had the briefcase on her cart and was taking it down to lost and found. He had little trouble inducing her to exchange it for a ten-dollar bill.

Robert was more than glad to get home that night. It had been one of the most exhausting days in his life.

While all this bungling was going on, the Ottawa Police began a thorough investigation of the latest Birks robbery. Working with Birks security, they got in touch with Sgt. Jim Corrigan in Toronto to tie this Birks robbery with those in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto and Sudbury. The security video tape of the two thieves in the Toronto robbery matched the description of the two men in the Ottawa holdup, but no identification was possible.

A partial thumb print taken from one of the surgical gloves discarded in Vancouver was compared with prints discovered on the Birks site in the Rideau Centre. Nothing conclusive came of this.

The best pieces of evidence the police had were the two shotguns left behind in Toronto and Vancouver. They knew if they could follow the trail of these shotguns back to the thieves who had stolen them, the path might lead them to the door of the Birks Bandit.

CHAPTER 13

Cafe

Two curious events occurred in Robert Whiteman’s life immediately after he robbed the Birks store in Ottawa. Four days after the holdup, Robert rented a houseboat from Garmac Houseboat Rentals in Pembroke. He was by himself and told the people at the marina he wanted to go fishing for the day. After being out on the Ottawa River for several hours, Robert brought the houseboat back in. He had caught no fish but had damaged the vessel on the port side. Readily admitting that he was responsible for the accident, Robert agreed to pay the deductible to have the vessel repaired. This he did with no complaint.

Eventually there would be some speculation that Robert was not fishing on that day. In due time, the real reason for his winter excursion out on the frigid water would become the subject of an intense police investigation.

Then, four days after the houseboat rental, he and Janice went on what he called a five-day business trip to the Bahamas. Although the trip appeared to be spontaneous and unplanned, it is curious that this is one of the few times he travelled with his wife and took his briefcase with him. Other than that, there was nothing extraordinary about their holiday. During their stay on the island, Janice sunbathed and read; Robert para-sailed and drank. The true purpose of this abbreviated trip to the Caribbean remains a mystery. Maybe it was just a spontaneous winter get-away like the others he so often liked to arrange. Or maybe this trip and the houseboat rental had something to do with the pieces of jewellery he had set aside for a rainy day.

While Robert and Janice were sunning themselves in the beautiful Bahamas, theories were percolating in Ottawa police circles. By now the Ottawa police had determined that the shotgun left behind at the Birks store in Vancouver was stolen from an Ottawa residence in 1985. That meant if one man was responsible for all the Birks robberies, as speculated by Metro Toronto’s Jim Corrigan, it was entirely possible that the Birks Bandit was from the Ottawa area.

Also unbeknownst to Robert Whiteman, another major police development was getting off the ground in Ottawa which would have serious repercussions on his future.

Since the fall of 1986, Detectives Snider, Heyerhoff and Robertson had been looking at a more p

roactive way of dealing with burglaries in the Ottawa-Carleton Region. Ottawa police were charging upwards of 750 thieves per year with B & E, but arresting these people and convicting them seemed to have little preventative effect. Every year the incidence of burglary would go right back up to where it had been the previous year. Furthermore, the recovery of stolen goods was negligible. It ran at less than 10 per cent.

The B & E detectives knew the market for inexpensive stolen goods was insatiable. Although a lot of it was peddled to homes in low rental housing communities, more and more of it was going into affluent houses where the over-taxed average citizen was looking for a good way to get around paying top retail dollar plus tax for his purchases.

In almost every stratum of society there was a growing willful blindness to the questionable origin of quality goods on sale for a cheap price. As the market for these goods increased, the traffic in stolen goods became immense.

Snider, Heyerhoff and Robertson could see that the way they were doing things with B & Es was not working. They were reacting to the crimes, solving lots of them but not preventing them from recurring. It was like being on a treadmill: they were expending a lot of energy but they were getting nowhere.

At one of their monthly meetings, an interesting idea emerged from their discussions.

“We’re never going to get anywhere chasing the little B & E thief. They’re like an army of ants – they just keep coming,” said Snider. “We got to go after the source.”

“Yeah, I agree,” Heyerhoff said. “The way we’re going now, we’re just chasing our tails around in circles. If we went after the fencing operations, we could knock ‘em on their ass.”

“They’ve tried that in the States,” Robertson added, “and it works. When they concentrate their efforts and go after the fences aggressively, it can disrupt their whole system, throw it in chaos. Eventually, they spend all of their time looking over their shoulders.”

“And most of the fences deal for drugs,” said Heyerhoff. “We could grab some of them by using drug charges.”

“How many fences do you think we’re talking about in this area, Ralph?” Snider asked.

“Geez, I don’t know. There’s got to be a ton of them. Sixty, maybe seventy. Maybe more.”

Snider was warming to the topic.

“If we start watching the B & E guys, they’ll take us to their fences. Once we see the operation, we can attack it.”

“We could go undercover and buy from them, sell to them too,” Heyerhoff added.

“You start going undercover and doing what you’re talking about, it’s going to cost a lot of money,” Robertson reasoned. “You’re talking about a whole project here.”

“Well,” Snider replied, “maybe that’s what we need. Maybe we need to put together a proposal for a project. What we’re doing now is getting us nowhere. Day in, day out, it’s the same old thing year after year. I’m getting tired of this crap. Aren’t you?”

Snider’s question was rhetorical. The three of them set about formulating the basis for a proposal that they could take to management, even though they knew it was a long shot.

Proposals like the one they had in mind were seldom popular with police management because, first of all, they highlighted an area where there was a glaring lack of success. Secondly, and more importantly, a proposal such as they had in mind would cost money and resources.

Where cost was concerned, management could be a problem for the cop on the street. Often referred to as bean counters, management’s primary purpose seemed to be watching the budget rather than doing what was effective. In fairness, they were in a tough spot too. Most new proposals that were brought to them had merit, but they required more policemen working longer hours, and budgets couldn’t always absorb the cost.

The fact that the proposal would be expensive wasn’t the only knock against it. Effective investigation against fencing had proven to be extremely difficult and management had so far shown little inclination towards putting extra resources into this area.

But the three detectives were not deterred. They began to formulate their proposal. It emphasized the fact that the fence was the foundation of the B & E empire. Without him, stolen property had little value. The break-in thief didn’t have the time, the energy, or the inclination to go around peddling all the goods he stole to many different individuals. He also couldn’t afford to be caught with it and needed to get it off his hands immediately. He had no use for it himself; how many televisions could he watch, how many VCRs could he use? Without the fence to buy his goods, the thief’s crime of break and enter was almost pointless.

Besides that, most B & E thieves were strung out on cocaine and counted on the fence to buy their goods with dope. This would give the police the opportunity to make some drug busts as well.

As the detectives drew up their proposal, they identified eightyseven fencing operations in the Ottawa area. They had names and addresses for all of them. These fences weren’t just working out of Ottawa bars and taverns. Their tentacles spread out through corner variety stores, grocery stores, jewellery stores, pizza outlets and restaurants. Most of the fences were high profile people, well known by the customers they served. Their popularity stemmed from their connections. They could provide a fabulous deal on anything a person wanted, from a car to imported French wine.

Snider, Heyerhoff and Robertson proposed to get all the police forces in the area involved. They knew that if they combined resources they could cover the entire region and go after all the fences in one fell swoop. Their idea was to create havoc on the streets by sowing distrust among the criminal element and disrupting the underworld’s way of doing business. If they could do that, they believed that the whole illicit system would fall into disarray.

Although their project would cover the entire Ottawa-Carleton region, its primary target would be Vanier, which was known in police circles as one square mile of hell.

Convinced that such a project would be worthwhile, the three detectives took their idea to Dave Rollins, head of the B & E squad with the Ottawa City Police. Rollins thought their plan had merit and talked it over with Snider’s Crime Unit Supervisor, OPP Corporal Bill Paterson.

As the proposal evolved it became clear that the OPP would have to fund the project, and all the other police departments, including the OPP, would be expected to commit manpower and such technical resources as vehicles.

When Paterson talked to Snider he was not completely encouraging. Although he saw some value in their idea, he did feel there were better places to put police time, money and energy. The best he could do was to say, “George, I’m not going to say it’s a dumb idea.” Then he added, “I’ll send it on.”

Paterson was responsible for putting their idea on paper. He structured their proposal into a simple four page document that outlined a joint forces operation that would:

a)Identify and prosecute as many thieves and fences as possible, and

b)Determine to whom the stolen property was being sold.

It further outlined the project’s requirements for manpower, vehicles, equipment, accommodations and financing. The proposal recommended the project commence in early spring and last for six months.

Paterson forwarded the proposal to the Criminal Investigation Branch at General Headquarters in Toronto. There it worked its way up the line to Deputy Commissioner William Lidstone. Accustomed to reading elaborate and detailed proposals up to two inches thick, Lidstone was so pleased to receive such a concise document he is reported to have reacted by saying, “At last! A proposal I can read on the john.”

Lidstone liked the proposal and sent it to Detective Inspector Lyle MacCharles, head of the CIB in Kingston, for development. MacCharles, using Paterson’s proposal as a guideline, wrote a thirty-four page operational plan for a proposed joint forces operation and sent it back to Deputy Commissioner Lidstone for his approval. The operational plan was called CAFE, an acronym for the phrase Combined Anti Fencing Enforcement.

<

br /> The operational plan that MacCharles drew up for CAFE was well organized and highly detailed. It was based on his communications with inspectors and superintendents from the Ottawa, Nepean and Gloucester police. Using intelligence information supplied by Snider and his colleagues, the plan named the nine major fences who were to be targeted. Tommy Craig was number one on the list.

Photo of Inspector Lyle MacCharles taken in 1980. He is reluctant to allow the use of a more recent photo because of his continuing investigations among the criminal element.

The CAFE team, February, 1988. Top row (L to R): Bill Van Kralingen, John Gardiner, Ralph Heyerhoff; Middle row: Jim McGillis, George Snider, Jack Richard, Mel Robertson; Front row: Dennis Tremblay, Scott Hogarth, Dan Mulligan, Bill Paterson.

The plan stipulated that the OPP and the Ottawa, Nepean and Gloucester police forces were to contribute two men each to the project. The detectives would work in pairs made up of combinations from various forces.

Two other OPP undercover police officers would be sent out to sell goods to the fences. Several of these items would be equipped with an electronic tracking device so that the police could trace the movement of the stolen property through the criminal network. Stolen goods were also to be purchased from the fences.

All operatives in CAFE were to be sworn to secrecy. No one, including their colleagues on the various police forces, were to know of the project’s existence. Because of the confidential nature of the work, CAFE could not afford to operate from a regular police office where their day-to-day activity could be observed by inquisitive officers who might compromise the secrecy of the project. Accordingly, a safe house was to be rented and used as a centre of operations. The safe house, whose existence and location was known only to CAFE members, would be furnished and equipped with state-of-the-art audio and video surveillance equipment. All relevant data pertaining to CAFE was to be entered into computers for information storage and retrieval.

The Flying Bandit

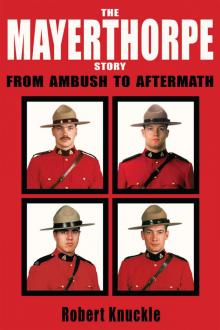

The Flying Bandit The Mayerthorpe Story

The Mayerthorpe Story